topics in elder law

- Pre-Probate

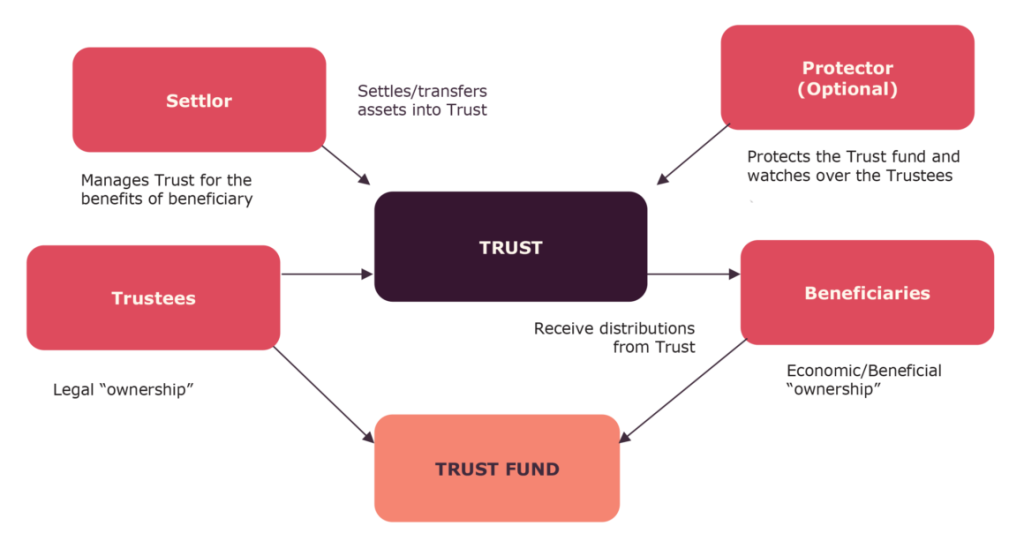

- Trusts

- Wills

- Advance Directives

- Paying for Long-Term Care

- Guardianship

- Power of Attorney

- Legal Implications of Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease

- Texas Elder Rights, Marital Issues, and the Homestead

references- Chapter 166 Advance Directives

- Health & Safety Code Section 166.082 Out-of-hospital Dnr Order; Directive to Physicians

- Chapter 49 Inquests Upon Dead Bodies

- Subtitle C Passage of Title and Distribution of Decedents’ Property in General

- ITS Publication 559 (2022), Survivors, Executors, and Administrators

- Texas Estates Code General Provisions Chapters 21–22

- Estates of Decedents Chapters 31–I Guardianship and Related Procedures Chapters 1001–1357 , Digital Assets Chapter 2001

- 26 U.S. Code Subchapter J – Estates, Trusts, Beneficiaries, and Decedents

Pre-Probate-When Death Strikes

10-2 Location of Death

A survivor and his or her family will react differently-and will need to react differently-depending on where the death of the loved one occurs. Absent an acci dent or murder, three basic options exist for the location of the death: at home, at a nursing home, or at a hospital.zzzz

10-2 :1 Home Death

Today’s widespread availability of hospice care enables many families to experience the death of a loved one at home. Hospice attempts to provide pain management and comfort care, without either delaying or promoting death.9

10-2 :1.1 Necessary Legal Documents

Families considering having their loved one die at home should arm themselves (on their loved one’s behalf) with at least the following documents:

- an Out-of-Hospital Do-Not-Resuscitate (DNR) order, to be used in the home to prevent emergency medical services (EMS) personnel from trying to resusci tate the deceased;10

- a Directive to Physicians and Family or Surrogates (also known as a Living Will), which will inform the attending physician and medical staff about the person’s wishes regarding life-sustaining treatment if he or she is in a terminal condition and unable to communicate his or her wishes regarding treatment;11

- a Medical Power of Attorney, which would, if necessary, allow the dying per son’s agent to make health care decisions on his or her behalf if the person is incompetent:;12 and

- an Appointment of Agent to Control Disposition of Remains, which spells out the dying person’s preference regarding burial and cremation, the type of funeral the person wants, and even the contents of the obituary.13

As we explained earlier in this text, the dying person would have executed these instruments while he or she still possessed mental capacity. He or she would have informed al least one family member about the location of these instruments.

10-3:1.2 Informing the Authorities

When a loved one dies at home, the survivor has several options on who to contact. Generally, these include the following:

- The hospice: It the decedent had been ill for some time, it is quite possible that his or her survivors would have arranged for hospice care. If the hos pice nurse is present at the home at the time the decedent dies, the death is deemed “attended,” just as it would be if the decedent had been under the care of a physician.14 The presence of hospice and the designation of the death as “attended” should be sufficient to spare the survivor the rigors of calling the police or EMS or having the Justice of the Peace for the precinct conduct an inquest into the death.15

If, however, the hospice nurse is not present at the time the patient dies, the survivor should call the hospice to report the death, and then follow their advice on what to do next. It may well be that the death would be labeled “unat tended,” needing investjgation by the police, the medical examiner, and maybe the conducting of an inquest.16

- The police: If the death was natural and expected, the police will complete a report form and contact the funeral home. However, if the death occurred under unusual circumstances, the police will investigate the death. A death investigator may investigate the scene of death and interview witnesses and medical caregivers.17 At this point, a Justice of the Peace for the precinct may conduct an inquest into the person’s death. If, however, the county is served by a medical examiner, the death investigator may call in the local medical examiner who may transrer the decedent’s remains to the medical examin er’s office.”‘ TI1e next step might be for the medical examiner to conduct an autopsy. Thereafter, the medical examiner will conduct an inquest into the decedent’s death.19

- EMS: Regardless of how well a caregiver has prepared for the pending death of someone, the actual death often elicits a call for EMS personnel. It is at this point that the survivor should be armed with the Out-of•Hospital DNR order and the Directive to Physicians, ready to assert the rights of the now-deceased

person who executed these instruments. EMS often transports the person’s remains to the hospital, where a physician examines the body and certifies the cause of death.

- TI,e fimerol home: If death is expected and the decedent and family had made pre.arrangements (such as the purchase of a funeral/burial plan) with a funeral home, the survivor may simply call the funeral home. The funeral director wiH arrange for the body”s transportation, a final examination, and certification of the death. Uthe decedent and his or her farnily had not made any pre-arrangements with a funeral home, the survivor may, at this point, do some comparison shopping to select a funeral home that fits his or her budget. 111e survivor should not rush into such an important decision.

10-3:2 Nursing Home Death

If a nursing home resident’s death is sudden, it may occur at the nursing home. Other wise, as the resident’s condition slowly deteriorates, the nursing home may transfer the resident to a hospital prior to death.

Generally, nursing homes do not have a place to store a resident’s remains. Neither does the home want to keep the dead body in the room for an extended period, espe cially if it is a semi-private room. Accordingly, if the decedent and his or her family had made pre.arrangements with a funeral home, the nursing home will call the funeral home to inform the funeraJ director about the death, whereupon the funeral home will transfer the remains. •

If, however, no pre-arrangements are in place with a funeral home. the nursing home may pressure the survivor to contact a funeral home quickly to come transfer the remains. Yet, the survivor should not be rushed into a decision! What he or she may do in this situation is determine whether the body could be moved to the coro ner’s office for temporary storage while the survivor selects a funeral home.

10-3:3 Hospital Death

Death in the hospital is often referred to as an ..attended death.” In such deaths, the circumstances are known, the causes well documented. In most cases, the attending physician will certify the death and release the body to the funeral home directly from the hospital’s morgue.

H, however, a person dies in a hospital and the attending physician is unable to certify the cause of death, the hospital’s manager is required to report the death to the local Justice of the Peace.WTuereafter, the Justice of the Peace (or medical examiner in larger counties) will conduct an inquest into the decedent’s death.21

- The Autopsy

An autopsy is not required in every death. Generally, autopsies are performed under two sets of circumstances: (1) the decedent’s surviving family members may ask for an autopsy (referred to in this text as an “elective autopsy'”)2’l or (2) the Jaw requires that a Justice of the Peace or medical examiner (in large counties or combinations of counties served by a medical examiner) order an autopsy to determine the cause and manner of death in cases of accident. homicide, suicide, and undetermined death.Zl If the decedent was an inmate within the state prison system, under certain circum stances. the Texas Department of Criminal Justice can also order that an autopsy be performed.24 For purposes of this text. we shall refer to the autopsies provided for by Texas law as “legally required” autopsies.

…

10-4 Organ Donation Issues

Once the decedent’s remains have been transferred to the funeral home, medical examiner’s office, or anywhere other than the scene of death, the survivor may wish to turn his or her attention to the issue of anatomical gifts.

…

l 0-6 Funeral Issues

Funeral issues are some of the most worrisome issues a survivor has to deal with tollowing the death of a loved one.

10-4 :1 Funeral Costs

As an initial matter, the issue of cost looms large for the survivor. According to the National Fut1eral Directors Association, the average cost of a traditional funeral in 2019 was $7,640.52 Jf the burial required the purchase of a vault, the average cost jumped to• $9,135-.53 For people who opt for cremation, the median cost in 2019 was

$5,150. These prices do not include cemetery, monument or marker costs, or miscel laneous cash-advance charges, such as for flowers or an obituary.55

,,,

10-6:2 Government Assistance

The federal government provides some assistance toward funeral and burial costs. These come in the form of either Social Security or Veterans Administration (VA) benefits.

1-6 :3 Cremation Issues

In some circles. a debate rages about the virtues of cremation compared with tradi tional burial. For a variety of reasons, many people today are turning to cremation. Earlier in this chapter, we discovered that cremal.ion costs less than burial. It is no wonder, then, that several cremation societi.es have sprung up all over the country. Indeed. some have sprung up in Texas where the average cost of a cremation is under

$1,000, much less than the average $10,000 it costs for a traditional burial.01

10-6:4 Death Certificates

The death certificate is a legal document that provides proof that a death has occurrecF3 TI1e certificate includes the date of death, the decedent’s Social Security number, and the name of the place and the specific number of the plot, crypt. lawn crypt. or niche in which the decedent’s remains will be interred or, if the remains will not be interred. the place and manner of other disposition.H The certificate also includes the cause of death, as certified by the attending physician75 or, if the death was not attended, by the person conducting the inquest into the decedent’s death.76 The medical certification part of the certificate can be amended following the conclu sion of an autopsy and receipt of the autopsy results.77

l 0-6:4.1 Obtaining Copies of the Death Certificate

The process of obtaining the death certificate is not too difficult for the surviving spouse. The surviving spouse answers some questions at the funeral home regard ing the decedent’s date of birth. parentage, and work history. The funeral director forwards that information to the hospital or physician who will be certifying the death. Once the doctor enters the cause of death and signs the certificates. Texas Department of State Health Services, Vital Statistics Unit, issues death certificates. The survivor pays for the certificates as part of the funeral costs paid to the funeral home. Indeed, in most cases, it is the duty of the funeral homed irector-as the person responsible for interment of the body or disposition or it if it is not being interred-to file the death certificate.78

Beyond the original copies issued to the survivor, the Vital Statistics Unit issues certified copies of death certificates to qualified parties for a fee.79 Qualified parties are limited to immediate family members (i.e., the decedent’s surviving spouse, children, siblings, parents, or grandparents) or people with a special relationship with the decedent (such as the executor of the decedent’s estate) who must provide legal documentation proving the special relationship.Pl’

10-6:4.2 Uses of the Death Certificate

111e death certificate is an important legal document that enables the decedent’s family members to close up the decedent’s business matters here on Earth. As an initial matter, receipt of the death certificate is necessary for the burial or other dispo sition of the decedent’s remains.81 Next, when the named executor of the decedent’s estate app1ies for probate of the decedent’s Last Will and Testament and of his or her estate, the named executor must provide proof to the court that the decedent has died.82 The decedent’s death certificate constitutes the best form of proof that the decedent has indeed died. Finally, the decedent’s survivors will also need copies of his or her death certificate to deliver to the bank, insurance company, stock broker, and other people with who they must now do business on the decedent’s behalf.

10-7 Administrative Issues

At the same time that he or she is addressing funeral issues, the survivor must also address important administrative issues. The proper approach to these issues will go a long way lo ensuring the smooth transfer of the decedent’s estate to his or her beneficiaries or heirs.

- : 1 Gather the Documents

TI1e survivor must, as soon as possible after the decedent’s death, gather the dece- dent’s original legal documents, along with any other vital information. Among other things, the documents may include (to the extent they exist):

- Last Will and Testament;

- codicil to any Last Will and Testament;

- Body Bequeathal Contract:

- pre-need funeral contract and burial instructions;

- Cremation Society membership;

- names, addresses, and telephone numbers of family members;

- Social Security number;

- pension documents for any survivorship payments;

- memoranda regarding the distribution of personal effects;

- Living Trust Agreement;

- amendments to living trusts;

- prenuptial agreement;

- postnuptial partition agreement;

- conversions to community property under Texas Family Code§ 4.102;

- Community Property Survivorship Agreement;

- Family Limited Partnership Agreement;

- pension survivorship rights:

- life insurance policies;

- automobile title(s);

- deeds to real property;

- residential leases:

- mortgages/liens against real property;

- notes receivable and payable;

- judgments of record;

- active litigation files;

- buy-sell agreements;

- partnership agreements;

- password lists for computer access;

- previous year’s federal income tax returns (IRS Form 1040. Form 1040A and necessary schedules) and identity of the decedent’s tax preparer;

- stocks and bonds:

- list of bank deposits: and

- decedent’s driver’s license.

10-7:2 Secure the Computer

The decedent would most likely have left a computer at home. However, the sur viving spouse may not be familiar with either the operation of the computer or the information stored on it Yet, the computer might contain financial data, family rec ords, the identity of heirs, or a computer address book with phone numbers and e-mail information. If the surviving spouse is not computer literate, he or she should retain the services (or help) of someone who can assist in the retrieval of this infor mation. ff this information reveals that the decedent had online subscription agree ments, the surviving spouse should dose them out. The surviving spouse would also have to decide whether he or she wants lo continue the decedent’s Internet access agreement.

At the very least, the surviving spouse should have the computer hard drive “wiped” dean by a computer technician before the spouse disposes of it.

10-7:3 Notifications

FolJowing the death of a loved one, the survivor faces the often unpleasant task of notifying various people and entities. Some of those notifications have legal implications.

10-7:3.1 Family Members

It is very important that the survivor notifies the decedent’s family members of his or her death. Some-if not all-of these family members may be beneficiaries in the decedent’s Last Will and Testament. Others just need to know, if for anything e]se. to preserve family harmony.

10-7:3.2 Obituary

The funera1 home normally asks whether the survivor desires an obituary. Obituaries are voluntary, yet can be quite expensive. \\’hether or not the survivor opts to have an obituary, and how long he or she decides it should be, is a matter of personal prefer ence. We simply note that the obituary has no legal significance and is not an official notice of the decedent’s death.

10-7:3.3 Power of Attorney

If someone other than the surviving spouse holds a durable power of attorney for the decedent, the surviving spouse shou1d inform that person about the death imme diately. After all, the agent’s authority under a durable power of attorney terminates upon the principal’s death.b.1 However, acts performed by the agent after the princi paJ’s death are valid if the agent was acting in good faith and was not aware of the principal’s death.61 It is important, therefore, that the agent be informed about the principal’s death as soon as possib1e lest he or she does something that contradicts the surviving spouse’s wishes.

10-7 :3.4 Clergy

After notifying the family. to the extent the decedent was religious, the survivor shoul call the loca1 religious leader of the decedent’s faith or house of worship. The survivor should seek to honor religious traditions important to the decedent. The survivor will typically find that the clergy may be deeply involved with the funeral, offering suggestions to honor traditional religious practices and meeting with family members to prepare a euJogy.

10-7 :3.5 Social Security

17,e Social Security Administration recommends that, as soon as possible after the death of someone who was receiving Social Security benefits, a family member shou1d:

- Notify Social Security of the beneficiary’s death. In most cases. the funeral director will report the person’s death to the Social Security Administration. To facilitate that, a survivor should give the funeral director the deceased’s Social Security number so he or she can report the death.t’-5 However, tJ1e survivor should still call the Social Security Administration’s toll-free number 0·800-772- 1213) soon thereafter to ensure the survivor’s benefits are properly processed.

- If the decedent had been receiving monthly Social Security benefits by direct deposits. the survivor should notify the bank or other financial institution of the beneficiary’s death. l11e survivor should also request that any funds received for the decedent for tile month of death and later be returned to the Social Security Administration.86

- If the decedent received benefits by check, the survivor should not cash any checks received for the month the decedent died or thereafter. Instead,. he or she should return the checks to the Social Security Administration as soon as possible.87

If the surviving spouse is receiving Social Security benefits on the decedent’s earn ings record. upon receiving notification of the decedent’s death, the Social Security Administration will change the payments to survivor’s benefits.88

If the survivor is already receiving Social Security benefits based on his or her own earnings record, he or she should apply for survivors benefits.119 This can be done during the survivor’s initial contact with the Social Security Administration. The survivor wiJI receive only one check, but it will be based on the bigger of the two earnings records.90

A surviving spouse receives full benefits at age 65 or older, or reduced benefits as early as age 60.91 A disabled widow or widower can receive benefits at ages 50-60.92 The survivor’s benefit may be reduced if he or she also receives a pension from a job where Social Security taxes were not withheld.93

10-7:3. 7 Other Pension Administrators

The surviving spouse should have information on other pensions the decedent received. lf that is not readily available. the attorney should ask to see the decedent’s copy of the previous year·s federal income tax return. Attached thereto should be one or more IRS Form 1099 that would identify the payor and give other account information.

10-7:3.8 Life Insurance Companies

lf the decedent owned life insurance policies, the survivor must locate each policy. The survivor should then contact the issuer to begin the paperwork to file a claim. The insurance company will mail the claim forms to the survivor. The survivor will complete the claim form and return it to the issuer, along with a copy of the decedent’s death certificate.

Texas law imposes certain deadlines on the insurance company as regards the receipt, investigation. and paying of the claim. The insurance company must acknowl edge the claim and start investigating it within 15 days of receiving written notice of the claim.101 As part ofits investigation, the company may request additional items and statements it reasonably believes it would need to make a determination reference the claim.1ccOnce the company has received all necessary information, it has another 15 days to notify the claimant in writing whether it will accept or reject the claim.103 Uthe company cannot meet these deadlines, it must inform the claimant of this inability, whereupon the company will have an additional 45 days to accept or reject the claim.101 If the company then rejects the claim, it must give the claimant written notice as to the reason why.105 If the company accepts the claim and agrees to pay, it must send pay ment within 5 business days of its informing the claimant that it would pay the claim.1<:..; All things considered and barring any further delays, the insurance company must pay the claim no later than 60 days after receiving the claim, proof of the beneficiary’s death, and documents confirming the rights of the claimants to the proceeds. w;

10-7:3.9 Tax Appraisal District

lf the survivor is the decedent’s spouse, he or she shou Id contact the local tax appraisal district as soon as possible after the decedent’s death.

lf a homeowner is receiving the 65-plus exemption108 and dies leaving a surviving spouse under age 65, the surviving spouse can continue the homestead exemption so long as he or she is 55 or older at the time of the decedent’s death, and (1) lives in and (2) owns the home and (3) applies to continue the tax exemption.H11 Appendix 18 contains an Application for Residence Homestead Exemption form.

10-8 Assets and Accounts that Pass Outside Probate

Many assets pass to survivors without going through the probate process. These assets range from items as simple as hank accounts to complex creations like the revocable living trust. In this section, we discuss some of those assets and look at how survivors could ensure that they receive the assets after the decedent’s death.

10-8:1 Bank Accounts

In Chapter 5, we discussed bank accounts and their function as resource management tools for the elderly. We return to them now to focus on hank accounts the proceeds of which can be transferred to a decedent’s survivor without going through the probate process. The survivor should determine whether he or she is a party on any of these types of accounts and should take appropriate action to have accounts transferred to his or her name where applicable. If the survivor is not sure about his or her owner ship status reference an account, he or she should ask the financial institution for a copy of the signature card. The card is actually a contract that will show whether the

survivor is entitled to become owner of the account now lhat the decedent has died. rt

the survivor is thus entitled, he or she should give a death certificate to the financial institution, whereupon it would release the funds to the survivor.

10-8 :1.1 Single Party Account With Payable on Death (POD) Beneficiary

As we discovered in Chapter 5, an elderly person who owns this type of account is, while still alive, the only person with authority to access it. Upon the eider’s death. however, the person or persons named on the account card as the POD beneficiary or beneficiaries become the owner(s) of the account.1IOThe POD arrangement super sedes anything the elder may say about the account in his or her Last Will and Tes tament. The account proceeds pass outside of probate, and are not included in the decedent’s estate.111

10-8 :1.2 Multiple Party Account Without Right of Survivorship

This type of account is commonly referred to as a ”joint account.” During the lifetime of all parties to the account, the account belongs to them all to their respective netcon tributfons to it-unless clear and convincing evidence exists that they intended other wise.112 In short., each person is entitled to what he or she deposited. minus what he or she withdrew, plus a proportionate share of the interest earned by the account.’13 Notwithstanding this ownership arrangement, any of the account owners may with draw any amount from the account at any time, and the financial institution will honor the withdrawal request.111 When one of the parties dies, his or her net contributions to

the account pass according to the terms of his or her wi11 or (in the absence of a will)

by the laws of intestacy.115

10-8:1.3 Multiple Party Account With Right of Survivorship

This type of account has all the features of the multiple party account without right of survivorship except that when an account holder dies, his or her share of the account passes to the surviving owners.116 However, this is so only because the parties to the account have a written agreement-signed by all parties including the decedent establishing the right of survivorship in the joint account117 The agreement normally contains language substantially similar to the following:

On the death of one party to a joint account, all sums in the account on the date of the death vest in and belong to the surviving party as his or her separate property and estate.118

No probate is necessary for the survivors to access the funds in the account. Nei ther a will nor the inheritance laws control the account. However, the IRS may seize the account to settle the tax debt of any of the owners.

10-8:1.4 Multiple Party Account With Right of Survivorship and Payable on Death Provision

The parties to this account own the account in proportion to their net contributions to it The financial institution may pay any sum in the account to any of the parties at any time. On the death of the last surviving party, ownership of the account passes to the POD beneficiary or beneficiaries.119

10-8:1.5 Trust Account

A trust account is an account with one or more persons named as trustee for the funds, and one or more persons named as beneficiary of those funds. During the life of the creator of the trust (referred to as the grantor or settlor), the funds belong to the trustee.12<) The beneficiary or beneficiaries have no rights to the account. The trustee may withdraw funds from the account.121 A beneficiary may not withdraw funds from the account before all trustees are deceased.l22 Upon the death of the last surviving trustee, ownership of the account passes to the beneficiary or bencficiaries.12.JAccord ingly, the trust account is not a part of the trustee’s estate and does not pass under the trustee’s will or by intestacy unless the trustee survives all of the beneficiaries and all of the other trustees.124

1-8 :2 Brokerage Accounts and Dividend Reinvestment Plans

When the decedent owned an investment account wherein he or she owned stock (such as with a brokerage account or a Dividend Reinvestment Plan) with an out-of state institution (as is the case with most Dividend Reinvestment Plans), the wording of the institution’s paperwork will determine what happens to the shares held by the decedent upon his or her death. For the account proceeds to pass outside probate, the paperwork must clearly indicate a right of survivorship or a POD designation; if it does not, the financial institution will in all likelihood demand Letters Testamentary and the asset will be subject to the probate process.

10-8:3 Automobiles

Texas now makes it relatively easy to transfer ownership of an automobile upon the death of the owner. Each Texas automobile title now contains a separate optional right of survivorship agreement that (1) provides that if the agreement is between two or more eligible persons, upon the death of one or more of the owners, the motor vehicle will be owned by the surviving owners; and (2) provides for the acknowledgment by signature, either electronically or by hand, of the persons.125 If the vehicle is regis tered in the name of one or more of the people who acknowledged the agreement. the title may contain a: (1) rights of survivorship agreement acknowledged by all the per sons or (2) remark if a rights of survivorship agreement is on file with the Department of Transportation.126 Upon the death of one of the owners (in our context, the elderly owner of the vehicle), the survivor can get title transferred to him or her by simply pre.sen ting the title and death certificate to the local tax assessor-collector’s office.12i

If the title lists both names but there is no right of survivorship, before transferring title, the tax assessor-collector will ask for Letters Testamentary, an Order Admitting Will to Probate as M uniment of Title, or an Affidavit of Heirship to a Motor Vehicle.izs

10-8 :4 Community Property Survivo.-ship Agreement

In 1987, Texas amended its Constitution so as to authorize community property survi vorship agreements.129 Stated simply, a community property survivorship agreement is an agreement between spouses creating a right of survivorship in community prop erty.130 When a married person who has executed such an agreement dies, his or her share of the community property described in the agreement passes to the surviving

spouse.131 Texas law holds that the agreement is effective lo pass title to the commu nity property without any further action.132

Nor.vithstanding the effectiveness of the agreement to pass title to the surviving spouse, Texas law provides that after the decedent’s death. the surviving spouse may apph• to the court for an order establishing that the agreement is valid and satisfies the requirements of the law.133 TI1is requires the surviving spouse to produce the orig inal community property survivorship agreement in court.131 Following the court’s adjudication that the community property survivorship agreement is valid, the surviv ing spouse must file the agreement with the County Clerk.135

Thereafter. the surviving spouse may sell any community property that he or she obtains through the community property survivorship agreement. but must wait 6 months after the date of the decedent’s death to make the sale.136 So long as the sur viving spouse has filed the agreement with the County Clerk. the purchaser is assured of good title.1J7

10-8:5 H the Survivor Spouse Receives Dividend Checks or Other Payments Made Out to the Decedent

Following the decedent’s death, it is possible for the surviving spouse to receive div idend checks or other payments made out to the decedent. These typically arrive in the mail. Should this happen. the surviving spouse has two options in dealing with these payments.

- First, the surviving spouse can return the payment, and request that a new check be issued to the “-estate of the decedent.”13f,

- Second, if a court of competent jurisdiction has already appointed an execu tor or administrator of the decedent’s estate and the check is either in pay ment for the redemption of currencies or for principal and/or interest on U.S. securities, payment for tax refunds, or payment for goods and services, the survivor can have the executor or administrator deposit the check in the dece dent’s account139 In endorsing the check, the executor or administrator must include, as part of the endorsement, an indication of the capacity in which the executor or administrator is endorsing. An example would be: “John Jones by Mary Jones, executor of the estate of John Jones.”140

If the decedent had an individual retirement account (IRA), if the financial institution distributes any proceeds to the beneficiary, the beneficiary will be obligated to include the amount received in his or her gross income for the year of receipt, and to pay all raxes due thereon.1-1i If the surviving spouse is the IRA beneficiary, he or she can roll over the IRA distribution into his or her own IRA. thus deferring the federal income tax.1-12 If the decedent had a large estate subject to the federal estate tax, the surviving spouse can defer the estate tax by utilizing the unlimited marital deduction.113

To receive the IRA proceeds or initiate the IRA rollover, the surviving spouse must contact the IRS trustee. He or she will need to supply the trustee with a copy of the decedent’s death certificate. Upon receipt, the IRA trustee will process the payment or IRA rollover.

10-8 :7 Trust Assets

If the decedent had executed a revocable living trust, it is likely that he or she named the surviving spouse as the successor trustee. This would minimize the procedures required to maintain the trust upon the decedent’s death. In reality, the ownership of this joint revocable living trust will not change; the trust will simply continue for the surviving grantor’s benefit. All assets in the trust will now be available to the surviving spouse-as they were while the decedent was sti11 alive.

If, however, the survivor is not named as the successor trustee, authority for man agement of the various trust assets will vest in the person who is named as successor trustee. In order to access the various trust assets, the successor trustee will need the original trust agreement and a copy of the decedent’s death certificate.

If the living trust contains credit shelter trust provisions, the successor trustee will have to re-title appropriate assets to fund the credit shelter trust The Elder Law attor ney will be able to guide the survivor in this process. If the successor trustee retains the same attorney who drafted the trust instrument, he or she will be familiar with the decedent’s intent in creating the trust, and will be able to advise the successor trustee in fulfilling it.

We note, however, that recent changes to tax law have made the credit shelter trust almost obsolete. One of the main purposes of a credit shelter trust is to limit estate taxes when the surviving spouse dies. Recent tax law changes have made the federal estate tax inapplicable to nearly all Americans. A certain amount of each per son’s estate is exempted from taxation by the federal government Under the most recent changes to this section of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC), the basic exclusion amount for the estate of a person dying between December 31. 2017, and January 1, 2026, is $10,000,000.H4 When adjusted for inflation pursuant to the provisions of the statute, us the amount was $11.4 million in 2019. TI1is meant that a decedent who died in 2019 with an estate valued at less than $11.4 million paid no federal estate tax.

Moreover, if the decedent had been married and had died withoul ever using any of his or her allowance, the surviving spouse could add the deceased spouse’s exclusion amount to his or her own.146 This means that for the decedent dying in 2019, S22.8 million dollars (the total value of both exclusions) is protected from federal estate tax ation without complex estate planning. Because most Americans do not have estates of that magnitude, the credit shelter trust-which used to be utilized to transfer assets to spouses to shield them from estate taxes-is slowly becoming obsolete.

…

10-9 :1 Determining Tax Issues Facing Decedent’s Estate

The first task the attorney retained to represent the personal representative has to ful fill as regards taxes is to determine the tax issues facing the decedent’s estate-and, by extension, the personal representative. These issues depend on several factors:

- Where was the decedent domiciled at the time of death?

- What was his or her marital status?

- ·what is the value of the decedent’s gross estate?

- Diel the decedent die testate, or did he or she die intestate?

- If the decedent died testate, to whom did the decedent leave his or her estate? Were there any charitable beneficiaries?

- Did the decedent die owing a tax liability to any trucing authority?

- At what point of the tax filing season did the decedent die?

- Did the decedent die after filing his or her income tax return?

- Did the decedent die before filing his or her tax return?

- Did the decedent die after the close of the tax filing season without having requested an extension to file the return?

- At what point of the tax filing season did the decedent die?

The importance of these factors arises out of one great and irreversible fact: Al the time of a person’s death, such person ceases to exist as a taxable entity. Indeed, as a result of the death, a newly created taxable e,ztity–called a,z estate-comes into being! Whether and when the decedent’s personal representative must file an income tax return for the decedent and/or the newly created taxable entity and the form or forms he or she needs to file depends on the point of the decedent’s tax filing season at which the decedent died.

10-9 :2 Filing Requirements and Forms Needed

In representing the personal representative professionally, the attorney must acquire a few forms from the IRS’s website (or from whatever tax preparation software product he or she uses). The attorney has no need to try and dazzle the client with reams and ’11S of useless forms; just stick to the basics-the forms one really and truly needs

•• the job done. The information in the following paragraphs presents a synopsis rnal Revenue Service Publication 559, Survivors, Executors a11d Administrators, sed and published on February 4, 2020. For more current information, please 1e IRS website at https://www.irs.gov/forms-pubs/about-publication-559.pdfl5J

10-10:2a Establishing the Estate-Form SS-4

The attorney’s-and the personal representative’s-first encounter with the Internal Revenue Service on behalf of the decedent occurs when they appJy for the estate’s Employer Identification Number (EIN). Whether the decedent died testate or intes tate, it is important that the personal representative obtains an EIN for lhe new tax able entity created by the decedent’s death. The application can be done by mail. by fax, or online at www.irs.gov. It is typically easier to app)y online. The personal representative–or the attorney acting on behalf of the personal representative-must be careful lo enter the decedent’s information EXACTLY as he or she had it on his or her last federal income tax return. For example, imagine a decedent who goes by the name “Vann Eze DerMann.” He signs his name that way, and as far as everyone is concerned, his name is “Vann Eze DerMann.” In reality, his name is ..Vann E. Zer mann,” and when he files his tax returns each year, that is the name he uses. If his personal representative is not aware of this bit of information, and thus does not relay the correct information to the attorney, they will most likely not be able to obtain the EIN for the estate. Hopefully, the death certificate would have the correct information and the error would be corrected.

1

Assuming the personal representative is aware of the intricacies of the decedent’s name and all other “secret information,” he or she-and the attorney-will be suc cessful, and the IRS will issue Form SS-4.

10-10:2b Form 56-Notice Concerning Fiduciary Relationship

Having obtained the EIN for the estate, the personal representative must now file Form 56, Notice Concerning Fiduciary Relationship, to inform the IRS of the creation of the fiduciary relationship under IRC § 690315 and provide the qualification for the fiduciary relationship under IRC § 6036.155 Note that Form 56 is not the same as, and does not serve the same purpose as, Form 2848. Form 2848 is for use by a taxpayer’s authorized representative in a controversy with the IRS.156 Although the fiduciary and the authorized representative may be the same person, a difference exists in the two roles:

- The fiduciary (who files Form 56) is treated by the IRS as if he or she is actu ally the taxpayer. Upon appointment, the fiduciary automatically has both the right and the responsibility to undertake alJ actions the taxpayer is required to perform. For example. the fiduciary must file returns and pay any taxes due on behalf of the taxpayer. m In the estate administration context, titles used for a fiduciary would be ..executor,” “administrator,” or ..trustee.”

- An authorized representative (who files Form 2848) is treated by the IRS as the agent of the taxpayer.’:.a He or she can perform only the duties authorized by the taxpayer. as indicated on Form 2848. An authorized representative is neither required nor permitted to do anything other than the actions explicitly authc rized by the taxpayer. In the estate administration context, an authorized repn sentative would be the attorney who represents the fiduciary or the accountar. or registered tax preparer retained by the fiduciary to prepare and file the ta’C returns. It is important to note that if the decedent had retained someone as an authorized representative prior to his or her death, that relationship ends upon the decedent’s death. That person can no longer speak for the decedent, and cannot speak for the estate unless the fiduciary appoints him or her as the authorized representative.

10-10:2c Decedent’s Final Form 1040 (or Intermediate

Form 1040, if Necessary)

If it is necessary that the personal representative files an income tax return for the decedent, the return will typically be due by April 15 folloruit,g the year of the dece dent’s death. However. that return may or may not be the only return to be filed by the personal representative.111e number of returns to be filed is dependent on just when the decedent died, and on what stage he or she was at vis-a-vis the tax filing season at the time of death.

…

10-10:2d Form 1310: Claiming a Refund for a Decedent

If the personal representative is claiming a federal income tax refund for the dee dent, he or she must file Form 1310, Statement of Person Claiming Refund Due a Deceased Taxpayer with the rcturn.168 The return preparer must attach a copy of the court certificate to the return showing that the personal representative was appointed to that office (testator or administrator). Strictly speaking, the Letters Testamentary or Letters of Administration should be sufficient to file with the tax return, but in the abundance of caution, it is wise that the personal representative file Form 1310 also.:””‘

lf, however, the decedent had been married and the person claiming the refund is the decedent’s surviving spouse filing a joint return with the decedent. the surviving spouse would not need to file Form 1310. i;o

10-10 :2e Form 1041: U.S. Income Tax Return for Estates and Trusts

The EIN issued to the personal representative will state the date by which the rep resentative must file the estate’s Form 1041. Form 1041 is used to file the following information:171

- the income, deductions, gains, and losses of the estate:

- the income that is either accumulated or held for future distribution or distrib uted currently to the beneficiaries;

- any income tax liability of the estate; and

- employment taxes on wages paid to household employees employed by the estate.

10-10:2f Form 8822: Change of Address

The attorney uses Form 8822 to notify the IRS of a change in the decedent’s mailing address. The attorney would, on behalf of the personal representative, file this form to have all correspondence from and with the IRS be sent to an address different to the decedent’s former address. This is necessary because, after all, the decedent is dead and no longer lives at the last known address the IRS has on file for him or her.

10-9 Income Tax Issues for the Estate, Fiduciaries, Survivors, and Heirs

111e following section focuses on the effect of an elderly person’s death on the income tax benefits, liabilities, and filing responsibilities of his or her survivors (including

…

his or her widow or widower), heirs, beneficiaries, estate, and fiduciaries. TI1e truth is that these effects are not limited to relatives and associates of the elderly, but can happen to anyone who has lost a loved one. Still, the focus of this book is the elderly.

10-11: 1 Income Tax Issues of Survivors and Heirs

The attorney should ensure that the decedent’s survivors and heirs are aware of the following income tax rules and principles that will affect them following their loved one’s demise:

- 1f the decedent qualified as some other person•s qualifying relative for the part of the year during which he or she was alive, the surviving taxpayer can claim the full tax benefits for the year regardless of when death occurred during the year.17

- Jf the decedent was married, his or her surviving spouse can file a joint return for the year of death and may qualify for special tax rates for the following 2 years if he or she has a dependent child by filing as ..qualifying widow(er) .”1i3 For the year that the decedent dies, the surviving spouse files a joint return with the decedent For the next 2 years, if the surviving spouse has a dependent child-but not a foster child-he or she can file as a ·•qualifying widow(er),” using the tax rates for a married couple filing joint.174

Generally, a survivor can file as a surviving spouse for this special benefit if

he or she meets all of the fo11owing requirernents:175

- The survivor was entitled to file a joint return with the decedent spouse for the year of de.ath, whether or not they actually filed jointly.

- The survivor did not remarry before the end of the current tax year.

- The survivor has a child or stepchild who qualifies as a dependent for the tax year.

- The surviving taxpayer provides more than half the cost of maintain ing a home. which is the principal residence of that child for the entire year except for temporary absences.

In short, a surviving spouse who does not have a dependent child living with him or her is not a qualifying widow or widower and must file as a surviving spouse. We note that the last year in which a surviving spouse can file jointly with, or claim an exemption for, a deceased spouse is the year of the decedent’s death.

10-11:2 Income Tax Issues of the Estate and its Fiduciaries

Before one can discuss the income tax issues facing the estate and its fiduciaries, one should first become familiar with some basic rules governing estates and their fiduciaries.

10-11 :2.1 Estate Basics

At the moment that a person dies, a new entity-the estate-comes into existence as a new taxpayer.

For income tax purposes, the estate begins with the probate estate. This “probate estate” includes all property that comes under the control or the personal represen tative by operation of either the will (where the decedent died testate) or state law (where the decedent died intestate)Y6

The estate begins on the date of the decedent’s death and continues until the final distribution of the assets is made to the beneficiaries.

10-11 :2.2 The Role of the Personal Representative

The personal representative oversees the estate. Typically, if the decedent died testate-that is, with a will-the personal representative is called an “Executor; if, on the other hand, the decedent died without a will, the personal representative is called an “Administrator.” The personal representative is responsible for:

- collecting and conserving all probate assets;

- paying all legitimate liabilities (including all truces);

- preparing all tax returns (or having them prepared); and

- distributing the remaining assets to the proper heirs or beneficiaries.

10-11:2.3 The Governing Instrument

To perform his or her duties properly, any fiduciary appointed by the will or by a court of competent jurisdiction must carefully read and evaluate the estate’s governing instrument. For the personal representative, that instrument is the decedent’s will.

The governing instrument of a trust is a trust document. If the trust is a testamen tary trust, it would be included in the decedent’s will. The trustee must be given a copy of the will that he or she may read and evaluate the terms of the trust.

If the decedent died intestate, the personal representative and the tax preparer should familiarize themselves with the intestacy laws of the state where the decedent was domiciled because these laws would constitute the governing instrument for the estate.

In the final analysis, then, the governing instrument, along with the appropriate state laws, will give guidance to the personal representative and the rax preparer on the following matters:

- identification of beneficiaries;

- distributions to be made to the beneficiaries;

- special allocations of income or expenses; and

- fiduciary accounting income.

10-11:2.4 Income of an Estate

To properly file Form 1041, the personal representative and the tax preparer must know and understand the income of the estate.

:\n estate’s taxable income includes all income from assets coming under the con trol of the personal representative during the period of probate administration, subject to the rules oi community property. m

The estate must also report income from items passing to the estate as a named beneficiary (or under state law-such as where a named beneficiary predeceased the decedent and no contingent beneficiary was named and therefore the property passed to the decedent’s estate).

Other circumstances that give rise to income include the following:

- If the decedent died owning personal property owned solely in his or her name, any income earned by such property is considered income of the estate. This is so because title to the property passed to the estate upon the decedent·s death. Ownership of the assets will not pass to the beneficiaries until the per sonal representative has distributed them to such beneficiaries.

- If the decedent’s will transfers solely owned personal property to a testamen tary trust, the estate will report the income from such personal property from the date of death until the time the property is lransferred to the trust. This transfer normally takes place at the end of the probate process.

- But note that if the decedent operated a business or farm up to the date of his or her death, the estate is not considered by law to operate the business or farm unless the will contains specific language directing the estate to continue the operation of this activity.

10-11:2.5 Income Reported-or Not Reported-by the Beneficiaries

In our Trusts and Estates class al law school, we learned that the will beneficiaries are the “natural objects of the testator’s bounty.” What are the income tax consequences for them of receiving this bounty-this property?

As an initial matter, the estate’s gross income does not include income from items passing directly to the decedent’s beneficiaries,178 or (under community property laws) the surviving spouse.

Following are some commonly encountered situations in which income from assets will not be subject to estate income taxation because it is paid directly to the estate beneficiaries:

- property owned jointly with right of survivorship;

- property registered as POD;

- employee death benefits and deferred compensation payable directl,yto desig nated beneficiaries;

- IRA Keogh, SEP-IRA. and other qualified retirement plans payable directly to a named beneficiary; and

- property tit1ed in the name of a living trust where the trust provides for the distribution to heirs.

10-12 Income, Deductions, and Exemptions

As the personal representative and the attorney/tax preparer sort through the dece dent’s paperwork to file his or her final Form 1040 and the estate’s Form 1041, they will be trying to determine which items constitute income, which ones constitute expenses–and, thus, deductions-and which ones are exemptions and thus neither reportable as income nor deductible therefrom. They will also have to determine which items must be reported on the final Form 1040, and which ones on the estate’s Form 1041. lf the taxpayer owned a business concern, the personal representative and the tax preparer will have to determine whether he or she ran it on a cash or accrual basis.111e following paragraphs offer some guidance on these issues.

10-12:1 Actual or Constructive Receipt and Disbursement

All income actually or constructively received before the death o.f the decedent is included on the final Form 1040.

All items paid before the death of the decedent are deducted on the final Form 1040.

10-12 :2 Income in Respect of a Decedent

All gross income that a decedent had a right to receive at death but was not actua11y or constructively received is not included on his or her final Form 1040 because these items are “IRD.”

If the decedent’s will does not designate a beneficiary of these lRD items, they are reported on the estate’s Form 1041 as income.179

If the decedent’s will names a beneficiary or the property is transferred by oper ation of law, then this IRD income is reported by the beneficiary on his or her Form 1040. ISO

10-12:3 Character of Income

In receiving and reporting income, it is important to note, and to maintain, the char acter of such income. The general rule is that the character of income received in respect of a decedent is the same as it would have been to the decedent if he o,r she were alive.181 For example, if the income would have been a capital gain to the

decedent. it v.ill be a capital gain to the estate-and to the beneficiary who eventually receives it.

10-12:4 Deductions in Respect of a Decedent

Ta>.-payers are a1lowed various deductions on their tax returns. Some deductions are personal. available to every taxpayer; others are available to taxpayers engaged in business enterprises. After the taxpayer dies and his or estate is going through the probate process, the personal representative and the attorney/tax preparer must make some decisions regarding these deductions. They have two principles to guide them:

- If the decedent had obligations before death that were not paid at the time of death, these items are termed “deductions in respect of a decedent.”182

- Items such as business expenses, interest, taxes, and income producing expenses for which the decedent was liable at death, but were not paid before death, are deducted by either the estate on Form 1041 or the beneficiary on Form 1040, as the case may be.183

10-12:5 Income and Expenses After Death

If the decedent used the cash basis method of accounting (as most people do), there would be both IRD and Deductions with Respect to a Decedent (DRD) for the income earned and expenses incurred before death but brought to light after the death of the decedent

10-12:6 Wages

On occasion, the personal representative receives wages for the decedent after he or she dies. There is a proper method of reporting such wages for income tax purposes.

First, we note that wages actually or constructively received prior to the decedent’s death are included on the final Form 1040.111-1Any wages received after the decedent’s death are IRD and are reported either by the estate on Form 1041185 or by the benefi ciary who receives said wages on his or her own Form 1040.181;

Next. note that the decedent’s Form W-2 Box 1, Income Subject to Federal Tax, to be used in preparing his or her final Form 1040 includes only the actual gross wages received. The Social Security and Medicare Wages, Boxes 3 and 5, include 100% of the actual amount and accrued amounts.

Third, the IRD is to be reported by the employer on Form 1099 MISC as non employee compensation in Box 3, and is not subject to self-employment tax.

Fourth, it is important to note that the term “wages” does not include any payment by an employer to a survivor or the estate of a former employee made after 1972 and after the calendar year in which such employee died.187 Hence, such payments are not subject to income taxation as wages.

10-12:7 Interest and Dividends

As regards interest and dividends, the rules are many:

- Amounts received prior to death are included on the final Form 1040.

- Any amount earned from the date of the last interest compounding date prior to death up to the date of death is IRD.

- Interest and dividends earned after death are reported by the estate on Form 1041 or by the beneficiary on his or her Form 1040.

- All dividends received prior to death are included on the final Form 1040.

- Any dividend declared before the decedent’s death but not received by then is HID and is included on the estate’s Form 1041 or the beneficiary’s Form 1040.

- Before reporting interest and dividends that should rightly be included on the decedent’s final Form 1040, the personal representative should ensure that he or she receives a Form 1099 evidencing the payment

- Likewise, the personal representative should receive a separate Form 1099 showing the interest and dividends includible on the returns of the estate or other recipient after the date of death and payable to the estate or other recip ient (i.e., the beneficiary).

- If the Form 1099 does not reflect the correct recipient or amounts, the per sonal representative should request a corrected Form 1099 from the payor.

10-12:8 Treatment of Self-Employment Income

If the decedent had been operating a sole proprietorship or was involved in a partner ship or some other form of business enterprise, the personal representative might be faced with self-employment income and self-employment tax issues. The attorney/tax preparer must be ready to give adequate representation:

- The attorney/tax preparer should report self-employment income actually or constructively received or accrued, depending on the decedent’s accounting method.

- For self-employment tax purposes only, the decedent’s self-employment income will include the decedent’s distributive share of a partnership’s income or loss through the end of the month in which deatl1 occurred.

- For this purpose only, the partnership’s income or loss is considered to be earned ratably over the partnership’s tax year.

10-12:9 Treatment of Rental Income, Expenses, and Depreciation

lf the decedent owned rental property, the income, expenses, and depreciation deduc tion thereof are treated as fo11ows:

- Income received and expenses paid prior to the decedent’s death are deducted on the decedent’s final Form 1040.

- Income accrued and expenses incurred prior to death are reported as IRD and DRD by the estate on the estate’s Form 1041 or passed on to the underlying beneficiaries also as IRD and DRD.

- Income received and expenses incurred after death are reported on the estate’s Form 104 l or passed on to the beneficiaries.

- Depreciation is prorated for the period ending on the date of the decedent’s death.

- Depreciation is based on a stepped-up fair market value on the date of death under the new statutory method and life.

- The estate is not permitted to elect IRC § 179 expensing on new personal prop erty acquired after the decedent’s death.

- The ..short year” rules for depreciation apply for any tax year the estate has that is less than 12 fu11 months.

10-12:10 Partnership Income or Loss: Partnership Closes Books on Decedent’s Date of Death

Uthe decedent had been involved in a partnership, the following rules would control the distribution of partnership income or loss:

- The tax year of the partnership closes for the partner on the date of the dece dent’s death.188

- The decedent’s income and losses up to the date of death would be reported on his or her final Form 1040.18′.)

- All income and loss after the date of death is reported on the estate’s Form 1041190 or the Form 1040 of the underlying bcneficiary.191

10-12:11 IRA and Pension Distributions: Decedent’s Distributions Prior to Death

Decedents sometimes die possessed with interests in pension plans and IRAs. Spe. cific rules exist on the tax issues arising from the existence of these interests. Some of these rules include the following:

- Distributions received prior to death are included on the decedent’s final Form 1040.192

- An amount distributable before death and received after death is IRD to the estate193 or designated beneficiary or beneficiaries,194 and js reported accord ingly.

- Distributions received after the decedent’s death are also IRD395 and are not subject to the 10% early withdrawal penalty even if the decedent was younger than 59.5 years at the time of his or her death or the recipient is younger than 59.5.196

- A surviving spouse who is named as the beneficiary of a decedent spouse’s IRA may roll the decedent’s IRA into his or her own traditional IRA. or, to the extent it is taxable, roll it over into a:

- qualified employer plan;

- qualified employee annuity plan (section 403(a) plan);

- tax-sheltered annuity plan (section 403(b) plan); and

- deferred compensation plan of a state or local government (section 457(b) plan), or treat himself or herself as the beneficiary rather than treating the IRA as his or her own.191

10-12 :12 Post Death Required Minimum Distribution

(RMD) Rules

After the decedent’s death, the IRA-whether the old one or the newly rolled over one-will eventually make distributions to the beneficiary. It is useful to know just how these distributions will be taxed.

First, if the IRA or qualified pension plan has a designated beneficiary, the remain ing account balance will be distributed over the remaining life expectancy of the bene ficiary whether or not the decedent died before or after the required beginning date.19,S

Second, if the plan does not have a designated beneficiary and the decedent dies after the required beginning date (generally April 1 following the year in which the decedent owner dies), the remaining balance is paid out over the remaining life expec tancy of the decedent owner of the IRA or qualified plan.

Retirement Topics – Beneficiary

Third, if the IRA or qualified plan does not have a designated beneficiary and the decedent owner dies before the required beginning date, the account balance must be distributed within 5 years after the year of the decedent owner’s death.199

10-12:13 Estate and Administration Expenses on Form 1041

The estate is entitled to a series of deductions on Form 1041. First are the estate administration expenses that would be deducted on the estate’s Form 1041. These are the expenses incurred as a result of the decedent’s death.

The IRC provides that estate administrative expenses should be deducted as expenses of the estate, and thus should be deducted on the estate’s Form 706, the Estate Tax Return. However, IRC Section 642(g) contains an election provision whereby an executor may “elect” to deduct administrative expenses on a timely filed Form 1041 (including extensions).201 The executor must also attach a waiver state ment that the estate will not deduct these expenses on the Estate Tax Return, Form 706. Section 642(g) also provides that these administrative expenses can be partially elected and waived, showing which expenses are being deducted on the estate’s Form 1041 while retaining the other administrative expenses on Form 706.102

U these expenses are deducted on Form 1041, any allocable expenses must be allo cated between exempt and non-exempt income. The amounts a11ocated to tax-exempt income are not deductible.203

Only the “reasonable” amounts for “administrativeH expenses are deductible on either Form 1041 or Form 706.20i

10-12:14 Funeral Expenses

Notwithstanding IRC § 642(g), funeral expenses are never deducted on either Form 1041 or Form 1040. They are deducted only on Form 706.205

10-12:15 Interest Expenses

The IRC allows the deductibility of interest expenses from the following sources:

- qualified mortgage interest;

- investment interest.;

- passive interest; and

- business interest.2(J(i

To the extent that a decedent incurred such interest expense during the year of his or her death, he or she is allowed these deductions on the final Form 1040 filed on his or her behalf.207

10-12:16 Charitable Contributions

Generally, taxpayers can make deductible charitable contributions of up to 50’¼ of their adjusted gross income.208 A decedent is no exception. However, any amounts not deducted on the final Form 1040 are lost. Charitable contributions are not trans ferable to the estate’s Form 1041 or to a beneficiary’s Form 1040. In short, charitable contributions made by the estate after the decedent’s death are deductible only if the decedent’s will provides that the contributions be paid out of the taxable income of the estate. This is true even if the beneficiaries agree that a contribution can be made from the estate funds.209

10-13 Texas Tax Issues

Although Texas does not have an income tax, it is possible for someone to die and for his or her survivors to face tax issues with state, county, or municipal authorities in Texas. It therefore behooves the personal representative-and the anorney repre senting him or her-to quickly try to settle these tax issues.

10-13:1 Property Tax Issues

The most common local tax issue decedents leave behind is the property tax. Dece dents typically owe real property taxes. If the decedent’s home is encumbered by a mortgage, the mortgage holder will settle the tax bill. But if the home .is not encum bered by a mortgage, it is the responsibility of the personal representative to contact the county tax assessor or county appraisal district and settle any outstanding prop erty tax liability.

In the event the decedent was a sole proprietor or the sole shareholder in an LLC or otherwise was the owner of a business enterprise, it would be quite likely that he or she also owed personal property taxes at the time of his or her demise. Once again, a visit to the county tax assessor of county appraisal district should lead to a resolution of these outstanding tax issues.

10-13 :2 Taxes Administered by Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts

The Texas Comptrol1er of Public Accounts administers 60 separate taxes. fees, and assessments in the state of Texas, including sales taxes collected on behalf of more than 1,400 cities, counties, and other local governments around the stale. The Comp troller also administers the franchise tax, motor vehicle taxes, and sales and use tax. If the decedent operated any type of business, the personal representative and his or her attorney should make an inquiry of the Office of the Texas Comptroller of Public

Accounts to determine whether the decedent died owing any taxes. lf the decedent dies owing any such taxes, the personal representative (using estate funds) must settle these liabilities.

10-14 Federal Wealth Transfer Taxes

There was a time when the federal wealth transfer taxes-the gift, estate, and generation-skipping transfer taxes-were of much concern to many Americans. In those days, the unified credit-that is, the amount of assets that each person is allowed to gift to other parties without having to pay gift, estate, or generation-skipping trans fer taxes-was significantly lower than it is today. Currently, the credit is very high. In 2019, for example, the credit was $11.4 million.210 The figure will be higher in 2020. The net effect is that few, if any people, currently pay the federal wealth transfer taxes. This may be good news to Texas, because Texas does not impose an inheritance tax either. Accordingly, any property someone living in Texas receives from a Texas dece dent is received free of any wealth transfer taxation.

see chapter pf